How many better ways of working have you uncovered lately?

This past year a lot of people have been forced into an unplanned and unwanted experiment. Many teams have had to figure out how to work in a remote-first way for the first time.

I was privileged to be working in a team that was already distributed, making the transition for us easier than many found it. But adapting to work without office equipment was still new.

Going without the offices that we were used to was uncomfortable in many ways. It was particularly difficult for those not privileged enough to have good working environments at home.

While nobody would wish the challenges of the past year upon anyone, disruption to the way we were used to working, helped us uncover some better ways. Nothing groundbreaking. But some things were driven home.

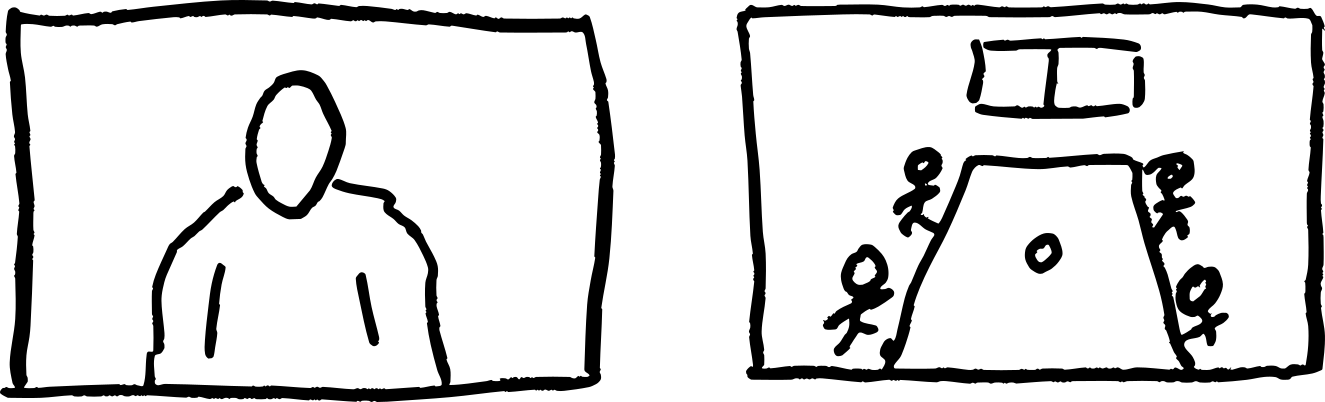

Like how much easier video discussions are when everyone is fully visible, at the same size on the screen, and close-mic’ed. Better than the hybrid experience when part of the team are using a conference room with shared microphone and camera.

We also learned how bad our open plan office environment was for collaborative working. Compared with the experience of two people pairing over a video chat, each in their own quiet spaces.

We had some resilience because we were already distributed. How much more resilient might we have been, had we been more used to experimenting and adapting the ways we worked, safely.

The opening sentence of the agile manifesto doesn’t seem to be as much discussed as the values & principles. I think it’s arguably the most interesting bit.

“We are uncovering better ways of developing software by doing it and helping others do it.”

The Agile Manifesto

This brings three questions to mind that might be useful reflection prompts:

- How many better ways of developing software have you uncovered recently? Have we already found the best ways of developing software? I hope not!

- Are the people who are developing software in your organisation, the same people who are uncovering better ways of doing it? Or does management tell people how to work?

- When deciding how to work, are you thinking foremost of what’s easiest for you? or what’s most helpful for others?

We didn’t need a pandemic to try the experiment of no office, but for many folks it was the first time trying that experiment. What if we experimented more? Experimenting with self-selected, smaller, low-risk experiments?

How much has your team changed the way it works lately? Could you be stuck in a local maximum? Are your ways of working best for your team as it is now, or tradition inherited from those who came before, who may have been in a different context?

Every person is different. Every team is different. Transplanting ways of working from one team to another may not yield the best working environment.

Ways of working often come from “things I’ve seen work before” or your preferences. Why would they be best for this team now? What are you doing to “uncover” what works best for you now?

Uncovering is a great metaphor. Move things around, remove some things, see what you discover!

Teams often limit themselves by only trying experiments where they believe the outcome will be an improvement. Improvement is then limited by the experience and imagination of those present.

How about trying experiments where you expect the result to be no different? Or where you have no idea what will happen? Or even where you expect the result to be worse?

Here’s some practical experiments you could try in your team to see what you learn:

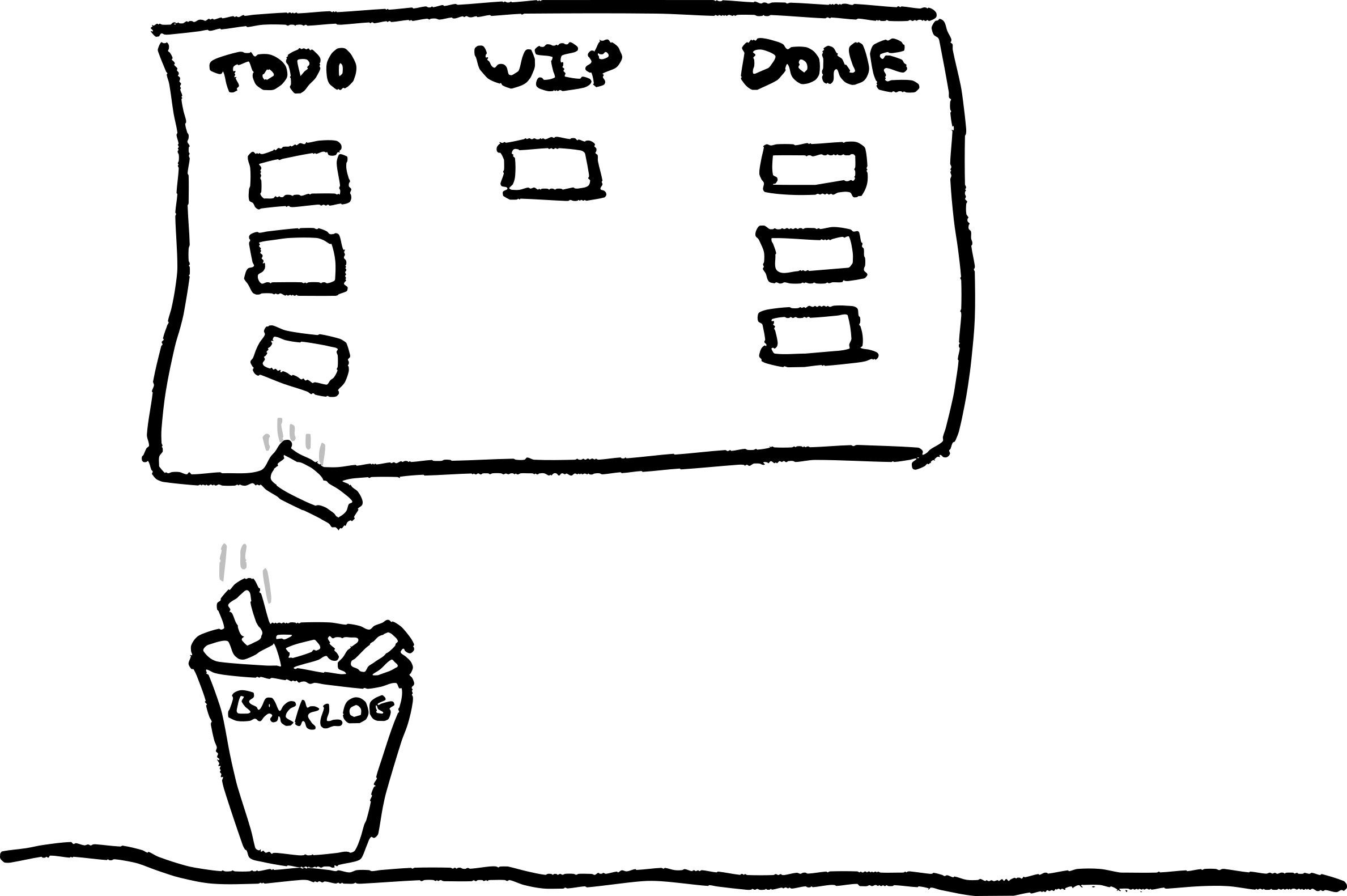

Try removing something

What activities, ceremonies, processes, and practices do you have? What would happen if you stopped doing one of them? They may seem like purely beneficial things. Even if they are, by trying to remove them you might learn more about their value (or lack thereof) to you. As well as their influence on your behaviour.

- Imagine there’s No Offices (We’ve had this experiment forced upon us lately)

- Imagine there’s No Meetings. Maybe we’d expect more miscommunications and wasted effort. Perhaps worth testing—maybe we’ll understand the value of meetings more clearly by abstaining for a time. Maybe we’d also learn to communicate asynchronously through writing more clearly.

- Imagine there’s No Estimates. Do you estimate all your upcoming tasks to measure progress? What would happen if you stopped doing it? If you’re required to give estimates what if you estimated everything as one day?

- Imagine there’s No Staging. Do you test your changes in a staging environment for a time before promoting to prod? What if you didn’t? How would you be forced to adapt to mitigate the risks you had been mitigating in staging.

- Imagine there’s No Branches. Do you work independently from others on your team? What if you had to all work on the same branch? How would you adapt?

- Imagine there’s No Backlogs. What if you discarded everything you’re not doing now or next? What would happen? Maybe worth trying.

- Imagine there’s No Managers. Do you know what your manager is doing? What would happen if they were unavailable for a while? How would your team need to adapt?

Removing things might seem risky and likely to make things worse. But what can we know about our resilience if we only do experiments where we think we know the outcomes.

It can be interesting to try removing something and see if we achieve similar outcomes without it.

It can help you understand the real value of the practice or process to your team. Help you understand your team better, and how things normally go right.

Try constraining something

Add an artificial limit on something you do often and see what you learn. Here’s some popular examples.

- Keep tests green at all times

- Implementation code may only be factored out of tests, not written directly.

- No more than 1 test in a commit

- Deploy every time tests go green

- Only one level of code indentation, or one dot per line

- Only mock types you own

- No fewer than 3 people work on a task if you usually work alone, or no more than 1 person working on a task if you usually work paired.

- No more than n tasks in progress

- Don’t start a new task until previous is in production.

- No changing code owned by another team.

Try the opposite

What ways of working do you tend to choose? What if you tried the opposite for a time and see what you learn? Try to prove it’s no worse and see what happens.

- Do you always take on the team’s frontend tasks? What if anyone but you took them?

- Work together in pairs? Try working apart individually.

- Work individually? Try working together in pairs.

- Feel we need to plan better? What if we just started without planning, together.

- Hiring to go faster? What if you tried having fewer people involved instead.

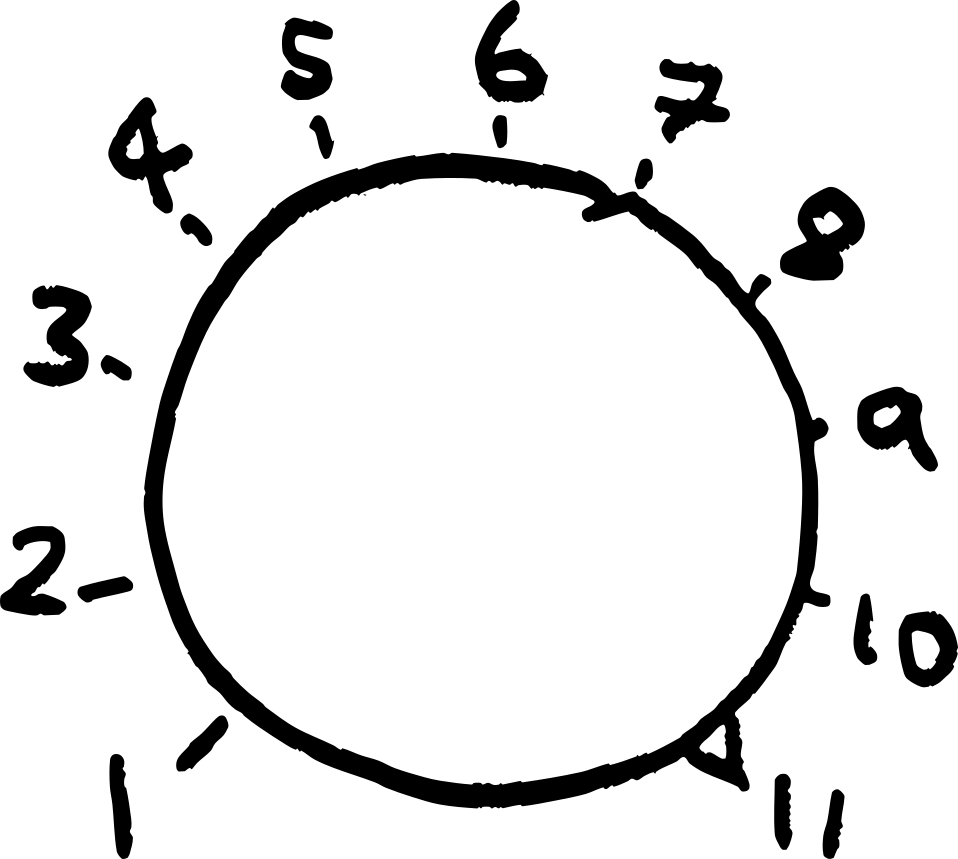

Try the extreme

An idea from extreme programming is to look for what’s working and then try to turn it up to the maximum; turn the dials up to 11.

A few ideas:

- Pair programming on complicated tasks? Try pairing on boring tasks too.

- Pairing? Try the whole team worked together as an ensemble/mob.

- Deploying daily? Try to deploy hourly.

- Do you declare a production incident when there’s a problem with customer impact? What if every “operational surprise” were treated as an incident.

Reflecting

Only run experiments that your team all consent to. Set a time limit and a reflection point to review.

Ask yourselves: What was surprising? Are we having more or less fun? What were the upsides? What were the downsides? Are we achieving more or less?

Make it the default to revert to the previous ways of working. Normalise trying things you don’t expect to work, and reverting. Celebrate learning that something is not right for you. If every experiment becomes a permanent change for your team, then you’re not really experimenting you’re just changing.

Be bold enough to try things that probably won’t work. You might uncover new insights into your team, your colleagues, and what brings you joy and success at work.