When I ask ask people about their approach to continuous integration, I often hear a response like

“yes of course, we have CI, we use…”.

When I ask people about doing continuous integration I often hear “that wouldn’t work for us…”

It seems the practice of continuous integration is still quite extreme. It’s hard, takes time, requires skill, discipline and humility.

What is CI?

Continuous integration is often confused with build tooling & automation. CI is not something you have, it’s something you do.

Continuous integration is about continually integrating. Regularly (several times a day) integrating your changes (in small & safe chunks) with the changes being made by everyone else working on the same system.

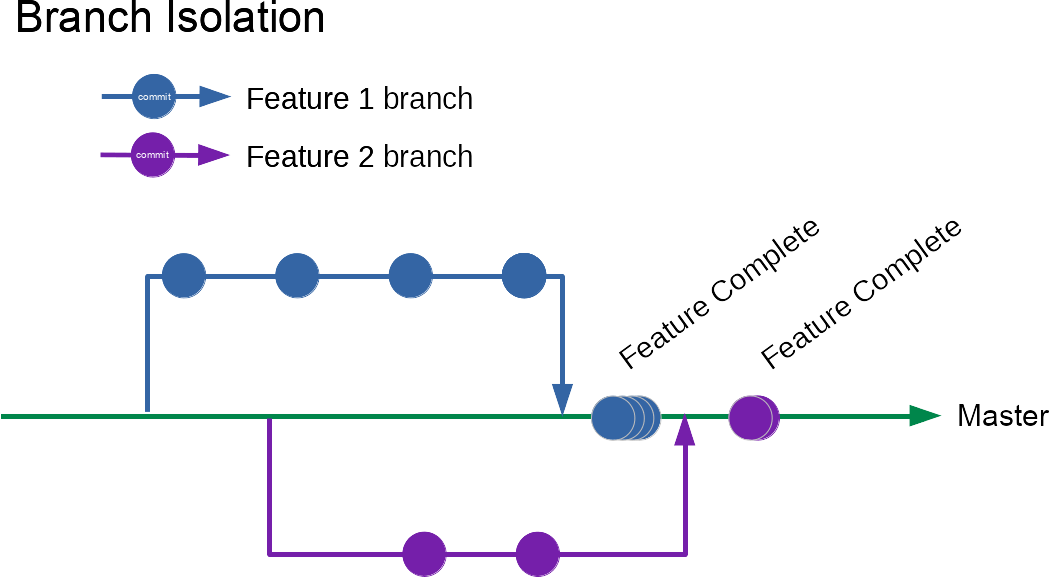

Teams often think they are doing continuous integration, but are using feature branches that live for hours or even days to weeks.

Code branches that live for much more than an hour are an indication you’re not continually integrating. You’re using branches to maintain some degree of isolation from the work done by the rest of the team.

I like the current Wikipedia definition: “continuous integration (CI) is the practice of merging all developer working copies to a shared mainline several times a day.”

I like this description. It’s worth calling out a few bits.

CI is a practice. Something you do, not something you have. You might have “CI Tooling”. Automated build/test running tooling that helps check all changes.

Such tooling is good and helpful, but having it doesn’t mean you’re continually integrating.

Often the same tooling is even used to make it easier to develop code in isolation from others. The opposite of continuous integration.

I don’t mean to imply that developing in isolation and using the tooling this way is bad. It may be the best option in context. Long lived branches and asynchronous tooling has enabled collaboration amongst large groups of people across distributed geographies and timezones.

CI is a different way of working. Automated build and test tooling may be a near universal good. (even a hygiene factor). The practice of Continuous Integration is very helpful in some contexts, even if less universally beneficial.

…all developer working copies…

All developers on the team integrating their code. Not just small changes. If bigger features are worked on in isolation for days or until they’re complete you’re not integrating continuously.

…to a shared mainline…

Code is integrated into the same branch. Often “master” or “main” in git parlance. It’s not just about everyone pushing their code to be checked by a central service. It’s about knowing it works when combined with everyone else’s work in progress, and visible to the rest of the team.

…several times a day

This is perhaps the most extreme part. The part that highlights just how unusual a practice continuous integration really is. Despite everyone talking about it.

Imagine you’re in a team of five developers, working independently, practising CI. Aiming to integrate your changes roughly once an hour. You might see 40 commits to main in a single day. Each commit representing a functional, working, potentially releasable state of the system.

(Teams I’ve worked on haven’t seen quite such a high commit rate. It’s reduced by pairing and non-coding work; nonetheless CI means high rate of commits to the mainline branch)

Working in this way is hard, requires a lot of discipline and skill. It might seem impossible to make large scale changes this way at first glance. It’s not surprising it’s uncommon.

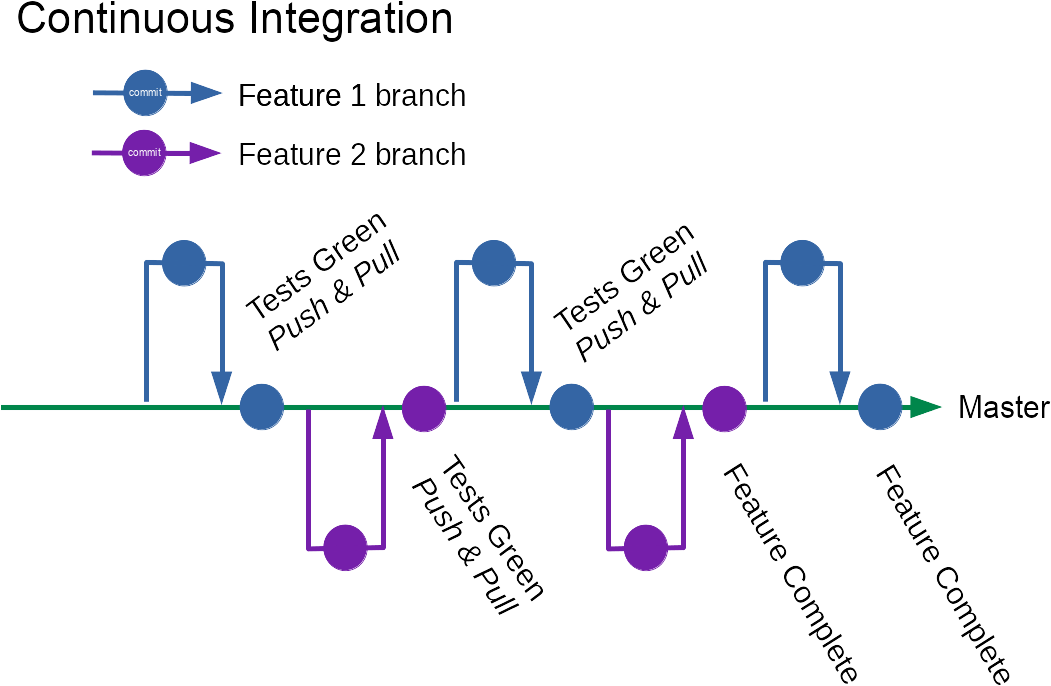

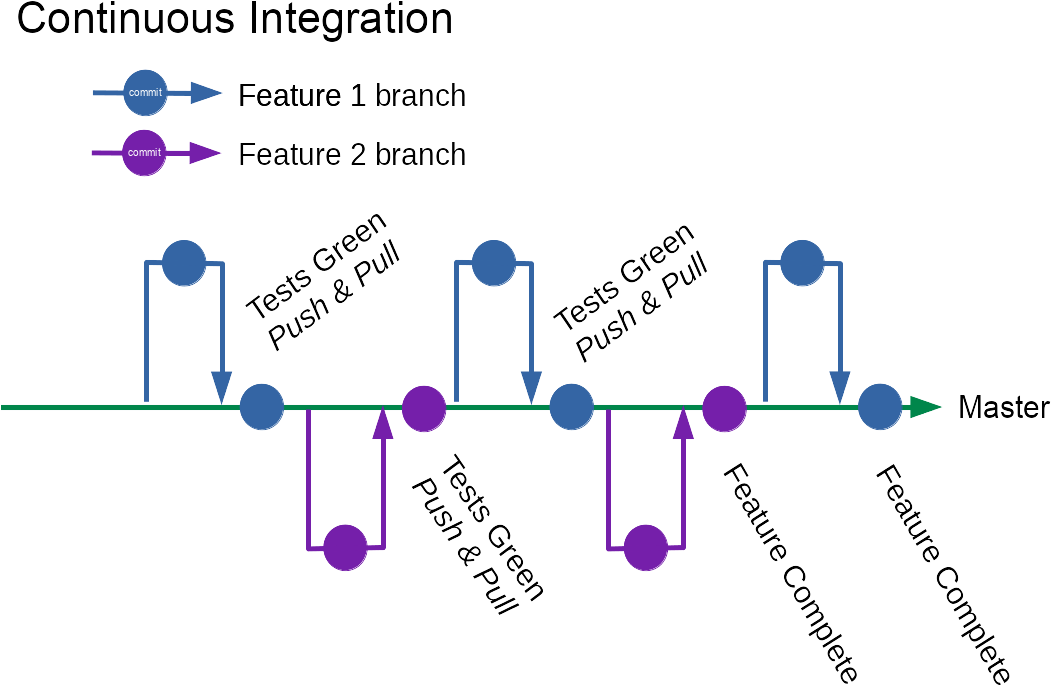

To visualise the difference

Why CI?

Get Feedback

Why would work work in such a way? Integrating our changes will incur some overhead. It likely means taking time out every single hour to review changes so far, tidy, merge, and deal with any conflicts arising.

Continuously integrating helps us get feedback as fast as possible. Like most Extreme Programming practices. It’s worth practising CI if that feedback is more valuable to you than the overhead.

Team mates

We may get feedback from other team members—who will see our code early when they pull it. Maybe they have ideas for doing things better. Maybe they’ll spot a conflict or an opportunity from their knowledge and perspective. Maybe you’ve both thought to refactor something in subtly different ways and the difference helps you gain a deeper insight into your domain.

Code

CI amplifies feedback from the code itself. Listening to this feedback can help us write more modular, supple code that’s easier to change.

If our very-small change conflicts with another working on a different feature it’s worth considering whether the code being changed has too many responsibilities. Why did it need to change to support both features? Modularity is promoted by CI creating micro-pain from multiple people changing the same thing at the same time.

Making a large-scale change to our system via small sub-hour changes forces us to take a tidy-first approach. Often the next change we want to make is hard, not possible in less than an hour. Instead of taking our preconceived path towards our preconceived design, we are pressured to first make the change we want to make easier. Improve the design of the existing code so that the change we want to make becomes simple.

Even with this approach we’re unlikely to be able to make large scale changes in a single step. CI encourages mechanisms for integrating the code for incomplete changes. Such as branch by abstraction which further encourages modularity.

CI also exerts pressure to do more and better automated testing. If we don’t have automated checks for the behaviour of our code it may break when changed rapidly.

If our tests are brittle—coupled to the current structure of the code rather than the important behaviour then they will fail frequently when the code is changed. If our tests are slow then we’d waste lots of time running regularly, hopefully incentivising us to invest in speeding them up.

Continuous integration of small changes exposes us to this feedback regularly.

If we’re integrating hourly then this feedback is also timely. We can get feedback on our code structure and designs before it becomes expensive to change direction.

Production

CI is a useful foundation for continuous delivery, and continuous deployment. Having the code always in an integrated state that’s safe to release.

Continuously deploying (not the same as releasing) our changes to production enables feedback from customers, users, its impact on production health.

Combat Risk

Arguably the most significant benefit of CI is that it forces us to make our changes in small, safe, low-risk steps. Constant practice ensures it’s possible when it really matters.

It’s easy to approach a radical change to our system from the comforting isolation of a feature branch. We can start pulling things apart across the codebase and shaping them into our desired structure. Freed from the constraints of keeping tests passing or even our code compiling. Coming back to getting it working, the code compiling, and the tests compiling afterwards.

The problem with this approach is that it’s high risk. There’s a high risk that our change takes a lot longer than expected and we’ll have nothing to integrate for quite some time. There’s a high risk that we get to the end and discover unforeseen problems only at integration time. There’s a high risk that we introduce bugs that we don’t detect until after our entire change is complete. There’s a high risk that our product increment and commercial goals are missed because they are blocked by our big radical change. There’s a risk we feel pressured into rushing and sacrificing code quality when problems are only discovered late during an integration phase.

CI liberates us from these risks. Rather than embarking on a grand plan all at once, we break it down into small steps that we can complete and integrate swiftly. Steps that only take a few mins to complete.

Eventually the accumulation of these small changes unlock product capabilities and enable releasing value. Working in small steps becomes predictable. No longer is there a big delay from “we’ve got this working” to “this is ready for release”

This does not require us to be certain of our eventual goal and design. Quite the opposite. We start with a small step towards our expected goal. When we find something hard, hard to change then we stop and change tack. First making a small refactoring to try and make our originally intended change easy to make. Once we’ve made it easy we can go back and make the actual change.

What if we realise we’re going in the wrong direction? Well we’ve refactored our code to make it easier to change. What if we’ve made our codebase better for no reason? We’ve still won.

Collaborate Effectively

Meetings are not always popular. Especially ceremonies such as standups. Nevertheless it’s important for a team of people working towards a common goal to understand where each other have got to. To be able to react to new information, change direction if necessary, help each other out.

The more we work separately in isolation, the more costly and painful synchronisation points like standups can become. Catching each other up on big changes in order to know whether to adjust the plan.

Contrast this with everyone working in small, easy to digest steps. Making their progress visible to everyone else on the team frequently. It’s more likely that everyone already has a good idea of where the rest of the team is at and less time must be spent catching up. When everyone on the team is aware of where everyone else has got to the team can actually work as team. Helping each other out to speed a goal.

No-one likes endless discussions that get in the way of making progress. No-one likes costly re-work when they discover their approach conflicts with other work in the team. No-one likes wasting time duplicating work. CI enables constant progress of the whole team, at a rate the whole team can keep up with.

Arguably the most extreme continuous integration is mob programming. The whole team working on the same thing, at the same time, all the time.

Obstacles

“but we’re making a large scale change”

We touched on this above. It’s usually possible to make a large scale change via small, safe, steps. First making the change easier, then making the change. Developing new functionality side by side in the same codebase until we’re satisfied it can replace older functionality.

Indeed the discipline required to make changes this way can be a positive influence on code quality.

“but code review”

Many teams have a process of blocking code review prior to integrating changes into a mainline branch. If this code review requires interrupting someone else every few minutes this may be impractical.

Continuous integration like requires being comfortable with changes being integrated without such a blocking pull-request review style gate.

It’s worth asking yourself why you do such review and whether a blocking approach is the only way. There are alternatives that may even achieve better results.

Pair programming means all code is reviewed at the point in time it was written. It also gives the most timely feedback from someone else who fully understands the context. Pairing tends to generate feedback that improves the code quality. Asynchronous reviews all too often focus on whether the code meets some arbitrary bar—focusing on minutiae such as coding style and the contents of the diff, rather than the implications of the change on our understanding of the whole system.

Pair programming doesn’t necessarily give all the benefits of a code review. It may be beneficial for more people to be aware of each change, and to gain the perspective of people who are fresher or more detached. This can be achieved to a large extent by rotating people through pairs, but review may still be useful.

Another mechanism is non-blocking code review. Treating code review more like a retrospective. Rather than “is this code good enough to be merged” ask “what can we learn from this change, and what can we do better?”.

Consider starting each day reviewing as a team the changes made the previous day and what you can learn from them. Or stopping and reviewing recent changes when rotating who you are pair-programming with. Or having a team retrospective session where you read code together and share ideas for different approaches.

“but main will be imperfect”

Continuous integration implies the main branch is always in an imperfect state. There will be incomplete features. There may be code that would have been blocked by a code review. This may seem uncomfortable if you strive to maintain a clean mainline that the whole team is happy with and is “complete”.

Imperfection in the main branch is scary if you’re used to the main branch representing the final state of code. Once it’s there being unlikely to change any time soon. In such a context being protective of it is a sensible response. We want to avoid mistakes we might need to live with for a long time.

However, an imperfect mainline is less of a problem in a CI context. What is the cost of a coding style violation that only lives for a few hours? What is the cost of temporary scaffolding (such as a branch by abstraction) living in the codebase for a few days?

CI suggests instead a habitable mainline branch. A workspace that’s being actively worked in. It’s not clinically clean, it’s a safe and useful environment to get work done in. An environment you’re comfortable spending lots of time in. How clean a workspace needs to be depends on the context. Compare a gardeners or plumbers’ work environment to a medical work environment.

“but how will we test it?”

Some teams separate the activities of software development from software testing. One pattern is testing features when each feature is complete, during an integration and stabilisation phase.

This allows teams to maintain a main branch that they think works, with uncertain work in progress in isolation.

However thorough our automated, manual, and exploratory testing we’re never going to have perfect software quality. Integration-testing might be a pattern to ensure integrated code meets some arbitrary quality bar but it won’t be perfect.

CI implies a different approach. Continuous exploratory testing of the main version. Continually improving our understanding of the current state of the system. Continuously improving it as our understanding improves. Combine this with TDD and high levels of automated checks and we can have some confidence that each micro change we integrate works as intended.

Again, this sort of approach requires being comfortable with main being imperfect. Or perhaps a recognition that it is always going to be imperfect, whatever we do.

“but we need to be able to do bugfixes”

Many teams work in batches. Deploying and releasing one set of features, working on more features in feature branches, then integrating, deploying, and releasing the next batch.

Under this model they can keep a branch that represents the current deployed version of the software. When an urgent bug is discovered in production they can fix it on this branch and deploy just that change.

From such a position the prospect of making a bugfix on top of a bunch of other already integrated changes might seem alarming. What if one of our other changes causes a regression.

CI is a fundamentally different way of working. Where our current state of main always captures the team’s current understanding of the most progressed, safest, least buggy system. Always deployable. Zero-bugs (bugs fixed when they’re discovered). Constantly evolving through small, safe steps.

A good way to make it safe to deploy bugfixes in a CI context is to also practise continuous deployment. Every micro-change deployed to production (not necessarily released). Doing this we’ll always have confidence we can deploy fixes rapidly. We’re forced to ensure that main is always safe for bugfixes.

“but…”

There’s also plenty of circumstances in which CI is not feasible or not the right approach for you. Maybe you’re the only developer! Occasional integration works well for sporadic collaboration between people with spare time open source contributions. For teams distributed across wide timezones there’s less benefits to CI. You’re not going to get fast feedback while your colleague is asleep! You can still work in and benefit from small steps regardless of whether anyone is watching.

Sometimes feedback is less important than hammering out code. If you’re working on something that you could do in your sleep and all that holds you back is how fast you can hammer out lines of code. The value of CI is much less.

Perhaps your team is very used to working with long lived branches. Used to having the code/tests broken for extended periods while working on a problem. It’s not feasible to “just” switch to a continuous integration style. You need to get used to working in small, safe, steps.

How…

Try it

Make “could we integrate what we’ve done” a question you ask yourself habitually. It fits naturally into the TDD cycle. When the tests are green consider integration. It should be safe.

Listen to the feedback

Listen to the feedback. Ok, you tried integrating more frequently and something broke, or things were slower. Why was that really? How could you avoid similar problems occurring while still being able to integrate regularly?

Tips when it’s hard

Combine with other Extreme Programming practices.

CI is easier with other Extreme Programming practices, not just TDD—which makes it safer and lends a useful cadence to development .

It’s easier when pair programming. Someone else helping remember the wider context. Someone to suggest stepping back and integrating a smaller set before going down a rabbit hole. Pairing also helps our chances of each change being safe to make. It’s more likely that others on the team will be happy with our change if our pair is on board.

CI is a lot easier with collective ownership. Where you are free to change any part of the codebase to make your desired change easy.

When your change is hard to do in small steps, first tackle one thing that makes it hard. “First make the change easy”

Separate expanding and contracting. Start building your new functionality in several steps alongside the old, then migrate existing usages, then finally remove the old. This can be done in several steps.

Separate integrating and releasing. Integrating your code should not mean that the code necessarily affects your users. Make releasing a product/business decision with feature toggles.

Invest in fast tooling. If your build and test suite takes more than 5 minutes you’re going to struggle to do continuous integration. A 5 min build and test run is feasible even with tens of thousands of tests. However, it does require constant investment in keeping the tooling fast. This is a cost of CI, but it’s also a benefit. CI requires you to keep the tooling you need to safely integrate and release a change fast and reliable. Something you’ll be thankful for when you need to make a change fast.

That’s a lot of work…

Unlike having CI [tooling], doing CI is not for all teams. It seems uncommonly practised. In some contexts it’s impractical. In others it’s not worth the overhead. Maybe worth considering whether the feedback and risk reduction would help your team.

If you’re not doing CI and you try it out, things will likely be hard. You may break things. Try to reflect deeper than “we tried it and it didn’t work”. What made it hard to work in and integrate small changes? Should you address those things regardless?